I

am indebted to a former Swedish ambassador to Japan for kindly lending me his personal copy of Fishing in Utopia — Sweden

and the Future that Disappeared to read over the 2019/2020

New Year's holiday. Had he not done so, I doubt if I

would ever have discovered this fascinating and unusual take on

life in Sweden by a fellow Brit.

I

am indebted to a former Swedish ambassador to Japan for kindly lending me his personal copy of Fishing in Utopia — Sweden

and the Future that Disappeared to read over the 2019/2020

New Year's holiday. Had he not done so, I doubt if I

would ever have discovered this fascinating and unusual take on

life in Sweden by a fellow Brit.

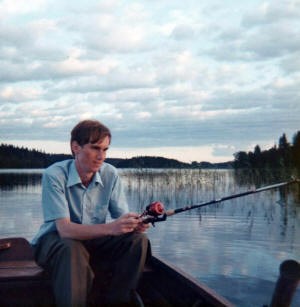

I first went fishing on a Swedish lake in August 1972, still just 17. Hooked on the country more than the fish, I returned the following summer and was destined to stay there for another 17 years.

Having settled in nicely some four years before Orwell Prize winner Andrew Brown's story begins, I can easily relate to the prevailing social and political milieus his writing brings back to me. His depictions of landscapes and the beauty of the countryside are also truly superb.

Storyline

Events are not always presented in chronological order, perhaps to offset any preconceptions. Only in chapter 8, for example, does Andrew Brown reveal he had already experienced Sweden in his pre- and early teens when his parents, both of them diplomats, had been assigned to Stockholm in the late sixties.

He reconnects with the country nearly a decade later at the age of 21 when he befriends Swedish carer Anita, 19, who is working with him at a Welsh nursing home. The following year he accompanies her back to Sweden. Apparently expelled from school and seemingly a disappointment to his parents, he turns his back on England to begin a new life fishing in “Utopia”, which the Swedish welfare state used to be held synonymous with, especially in the sixties and seventies.

Accepting a rather monotonous job at a timber mill and writing articles for a living, he eventually marries Anita, whose working and social life appears to be more stable and secure than his own. Their roles have been reversed. She now thrives on her home turf. He is the outsider.

As the author gets to know the country better, he becomes conscious of the social effects of decades of Social Democratic Party de facto one-party rule. As early as pages 17–18, read his thoughts on the small community of Nödinge (now expanded into Nödinge-Nol) some 20 kilometers northeast of Sweden's second largest city and principal port Gothenburg:

“The first thing that struck me was the loneliness…. I’ve never lived in, nor could imagine, a place where people talked less to each other…. It wasn’t deliberate unfriendliness. People just didn't know how to talk to one another.”

Fishing becomes his regular escape from conformity and uniformity. But, as disillusionment grows, his marriage breaks down and he withdraws to London, which he now sees in a more positive light.

A further two decades pass before he returns to find a very different Sweden, one that has lost much of its manufacturing industry and hence its ability to afford very high taxes. The concept of “Swedishness” has also changed with the influx of poor, under-educated asylum-seekers from beyond Europe’s borders who are swiftly granted Swedish citizenship but not well assimilated.

Peace-loving Sweden is also having to confront a dramatic rise in violent crime unimaginable in the past. The prime minister (Olof Palme) has been assassinated on a Stockholm street. Many Swedes now feel they have lost their sense of direction.

In search of the indigenous Swedish culture that once so enticed him, Andrew Brown heads to traditional midsummer celebrations in Lannavaara in the extreme far north. He also seeks solace in old familiar fishing spots.

He satisfies his curiosity, only to realize that he, too, has changed. On the final page he concludes:

“I understood I had no business there any longer.”

Oh, what a sad ending!

Overall assessment

The book was original, compelling, hard to put down, and certainly deserves four stars out of five. I love the sumptuously rich nature descriptions and intricate detail about fishing. What I am missing is a bit more factual information about the country, and perhaps some fresh ideas for its future. Neither a fishing fanatic nor a Sweden enthusiast will likely be 100% contented with this book, but fairly close.

Brown's most detailed personal portrait is that of his wife’s mother Anna, whom he appears to admire tremendously as a true champion of the old pre-industrial Sweden and its austerity, as immortalized by historical novelist Vilhelm Moberg. We learn comparatively little about ex-spouse Anita, which must disappoint readers wishing to know more about the joys and challenges of an international marriage. At times, the author comes across as emotionally distant and I was not swept away by his story in the way I was hoping to be. Nevertheless, his writing it all down must have been highly therapeutic as he strove to come to grips with his past.

I had personal experience of several things he touches upon. For example, it could indeed be difficult for a non-Nordic citizen to get a Swedish work permit in the pre-EU early seventies because of local resistance from labor unions, who usually had the final say in such matters. The only way for a Brit to stay longer than three months back in those days was through personal connections, either business or private. Since Brexit we have come full circle.

I can also vouch for the co-operative spirit but sometimes oppressive nature of the close-knit small town and rural communities. It seemed to me that everyone knew everyone, and success was based on each individual knowing what to do — and what not to do. There was Lutheran-inspired order, and little sympathy for those who were felt to have gone astray.